Species profiling - Tiger shark

This blog presents an overview of the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), covering its morphology, distribution, behavior, feeding ecology, reproduction, and conservation status. Drawing from peer-reviewed literature and field observations in Fuvahmulah Atoll (Maldives), this review aims to consolidate scientific understanding of the species and highlight its ecological significance in tropical marine ecosystems.

Taxonomy and Classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Chondrichthyes

Order: Carcharhiniformes

Family: Carcharhinidae

Genus: Galeocerdo

Species: G. cuvier

Tiger sharks are the only extant member of the genus Galeocerdo and represent a highly distinct lineage within Carcharhiniformes (Compagno, 2001).

Evolutionary history

The tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) is the only extant species in the genus Galeocerdo, a highly distinct lineage within the requiem shark family Carcharhinidae (Compagno, 1988). Fossil evidence traces its origin back to the Eocene epoch (~56–34 million years ago), with fossilized teeth resembling modern tiger sharks found on every continent except Antarctica (Kent, 1994). The structure of these fossil teeth suggests a slow evolutionary rate and an early specialization in cutting through hard-bodied prey.

Genetic studies show that G. cuvier diverged early within the Carcharhinidae, with phylogenetic analyses placing it at a basal position in the family tree (Naylor et al., 2012). This distinct evolutionary lineage may explain the tiger shark’s behavioral and ecological flexibility, including its wide-ranging habitat tolerance and broad diet.

Due to its long fossil history, stable body plan, and ecological niche retention, Galeocerdo cuvier is sometimes referred to as a "living fossil", although the term is informal and not phylogenetically rigorous (Ebert et al., 2021).

Morphology and Physiology

Tiger sharks are among the ocean’s largest predators, typically reaching 3.25–4.25 m in length, with records up to 5–6 m, and exceptional individuals near 7.5 m. Adult weight typically ranges from 385–862 kg, though some rare specimens exceed 900 kg

Sexual dimorphism is present: females average 2.92 m, males around 3.20 m, with females generally larger at maturity

Juveniles exhibit distinct dark stripes and blotches along a blue-green dorsal side, fading as they mature; ventral surfaces are light yellow or white (countershading)

Their snout is broad and blunt, head wedge-shaped—optimized for hydrodynamics and rapid turning

They possess a heterocercal tail (upper lobe longer than lower), aiding lift and agility in water

FINS

1. First Dorsal Fin

Large and prominent, located midway along the back.

Serves to stabilize the shark during swimming and prevents rolling.

Often visible above the surface when cruising near the top of the water column.

2. Second Dorsal Fin

Much smaller than the first, located near the tail.

Assists with minor corrections in stability, especially during slow turns or vertical movement.

3. Pectoral Fins (Pair)

Broad and wing-like, positioned just behind the gill slits.

Provide lift and steering—critical for maneuvering and maintaining depth.

Used for gliding and making tight turns during predatory strikes.

4. Pelvic Fins (Pair)

Located on the underside of the body, behind the pectoral fins.

Help with stabilization, especially during slow swimming or hovering.

Also important for positioning during mating.

5. Anal Fin

A small fin on the underside, located between the pelvic fins and caudal fin.

Helps reduce yaw (side-to-side movement) and keeps the shark steady.

6. Caudal (Tail) Fin

Heterocercal shape: upper lobe is longer than the lower lobe.

Generates most of the shark's forward propulsion through powerful side-to-side strokes.

The asymmetry provides lift as well as thrust—essential for buoyancy control in sharks, which lack swim bladders.

Reproduction & Life History

Males

Maturity Size: Males reach sexual maturity at 2.2–3.0 meters in length.

Maturity Age: Typically between 4 to 6 years, though this may vary by region.

Claspers: Males possess paired claspers—elongated extensions of the pelvic fins—used to deliver sperm into the female during copulation.

Behavior: During mating, males often bite the female to maintain grip—a common shark courtship strategy.

Reproductive Role: Males do not participate in parental care. Their role ends after copulation.

Females

Maturity Size: Females mature later and larger than males—typically around 3.3–3.5 meters.

Maturity Age: Generally between 6 to 8 years.

Gestation Period: One of the longest among sharks—13 to 16 months.

Litter Size: Females give birth to 10 to 80 pups, making tiger sharks among the most fecund large shark species.

Birth & Development: Pups are live-born, measuring about 50–90 cm in length. Immediately after birth, they are fully independent and receive no maternal care.

Reproductive Frequency: Most likely biennial, with long recovery periods due to the energetic cost of gestation.

Why do we majorly see females tiger sharks in Fuvahmulah?

The dominance of female tiger sharks in Fuvahmulah is likely due to sexual segregation, a common behavior in many shark species where males and females inhabit different areas based on reproductive roles and ecological needs. Fuvahmulah offers deep, warm waters with abundant prey and minimal human interference ideal conditions for large, mature females, particularly during gestation. Females may use the island as a foraging and resting ground while avoiding males outside the mating season to reduce harassment and energy expenditure. The consistent presence of the same individuals suggests site fidelity, making Fuvahmulah a key location in their migratory or reproductive cycle.

Gestation period

Tiger sharks have one of the longest gestation periods among sharks, lasting around 13 to 16 months. They are aplacental viviparous, meaning embryos develop inside eggs that remain within the mother's uterus, but instead of a placenta, the pups rely on a nutrient-rich yolk sac for nourishment. As the embryos grow, they absorb the yolk and are also bathed in uterine fluids, which may provide additional hydration. There is no direct blood connection between the mother and the pups. Once fully developed, the mother gives birth to a litter of 10 to 80 live pups, each about 50–90 cm long, fully formed, and immediately independent. This long, energy-intensive process likely explains why females seek out rich, undisturbed environments like Fuvahmulah during gestation.

Conservation Status

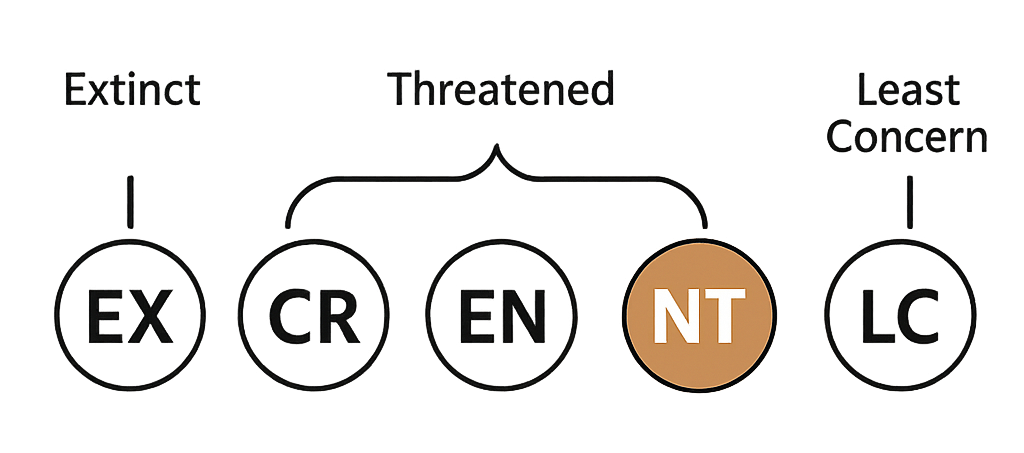

The conservation status of a species reflects its risk of extinction, as assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. Categories range from Least Concern (LC) for species at low risk, to Extinct (EX) for those that no longer exist in the wild or at all. In between are varying threat levels: Near Threatened (NT), Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), and Critically Endangered (CR). These classifications help scientists, conservationists, and policymakers understand species’ survival prospects, track population trends, and prioritize conservation efforts to protect biodiversity.

tiger sharks are currently listed as Near Threatened (NT) on the IUCN Red List. a category that signals an urgent warning: while they are not yet endangered, they are heading in that direction if current trends continue. The reasons for their decline are entirely human-driven and, frankly, absolutely unnecessary.

Overfishing and Targeted Hunting

Tiger sharks are caught for their fins, which fetch high prices in certain markets, and for their meat, skin, and liver oil.

In some regions, they are deliberately targeted in “shark control” programs, a misinformed approach that does more harm than good to marine ecosystems.

Bycatch in Commercial Fisheries

Longlines, gillnets, and the big trawls catch tiger sharks unintentionally while targeting other fish species.

This accidental capture is one of the largest sources of mortality, especially for juveniles.

Slow Reproductive Cycle

Females carry their young for 13–16 months and give birth to relatively small litters.

This means populations recover very slowly even if fishing pressure is reduced.

Loss of Large Breeding Adults

Commercial fishing often removes the largest, most reproductively valuable individuals first.

This skews population structure and reduces overall breeding success.

Habitat Degradation

Coastal development, pollution, and changes to prey abundance make it harder for tiger sharks to thrive in traditional hunting grounds.

The Dangerous Predator misconception

The public image of tiger sharks has been heavily distorted by sensationalist media. While they are large, curious, and capable predators, attacks on humans are extremely rare. And when they do happen, they are almost never deliberate hunts rather:

Mistaken Identity: Murky water, poor visibility, or splashing can make a swimmer or surfer resemble a natural prey item.

Investigatory Bites: Sharks explore the world with their mouths. A single bite is often enough for them to realize a human isn’t worth eating. unfortunately, even a single bite can cause injury.

Human Behavior: Many incidents occur when people ignore safety guidelines, swim in areas with known shark activity, or handle baited fish in the water.

They Don’t Eat Humans - Here’s What They Do Eat

Tiger sharks are opportunistic feeders with a broad diet: fish, squid, seabirds, sea turtles, and even the occasional marine mammal. Their hunting strategy is built on patience and precision:

They use stealth, swimming slowly to avoid detection.

They have exceptional senses, detecting electrical signals and vibrations from prey.

They rely on close-range inspection, often circling before making a move.

Humans are simply not on their menu, and any interaction that turns negative is more a reflection of human misjudgment than shark aggression.

Why Protecting Them Matters

Tiger sharks are apex predators, meaning their presence regulates the balance of entire marine ecosystems. Removing them can cause prey populations to explode, which in turn disrupts coral reefs, fish stocks, and the ocean’s natural order. Protecting tiger sharks isn’t just about saving one species. it’s about safeguarding the health of our oceans.

How Our Expedition (One-Atoll) Changes the Narrative

At Nereus Expedition, our mission goes beyond showing people tiger sharks. we aim to change the way the world sees them. The “man-eater” myth has been told for decades, but out in the open ocean, the truth becomes impossible to ignore. Through our carefully designed encounters, guests don’t just see tiger sharks - they experience them as they truly are: powerful, graceful, curious, and vital to the health of the marine ecosystem.